a quick study

on mastery, magic, and making in the age of AI

My parents always indulged my creative whims as a child, with one notable exception: when I wanted to pick Art as one of my GCSE options.

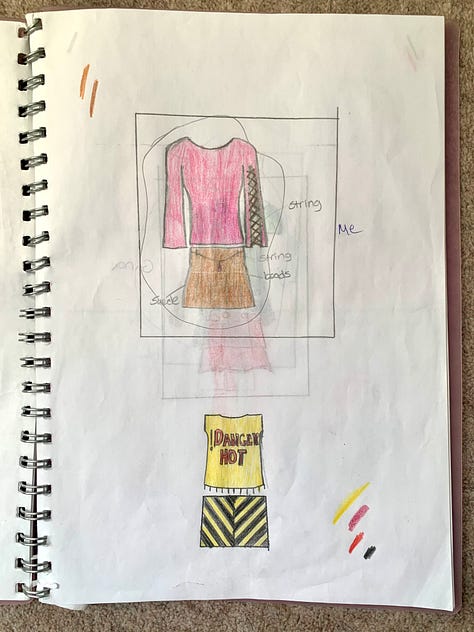

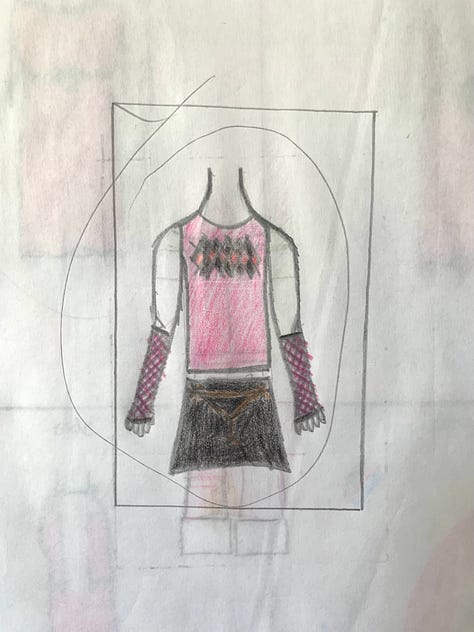

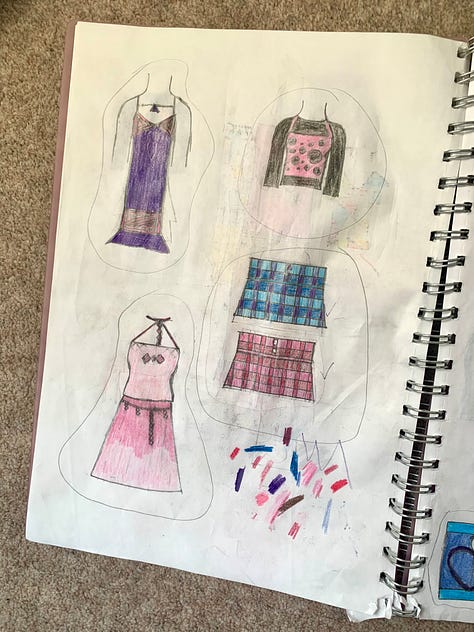

Their hesitation wasn’t unfounded. I have childhood notebooks from my aspiring Fashion Designer phase, page-upon-page filled with (terrible) sketches of outfits that could only have been thought en vogue by a Millennial school girl of the Lizzie McGuire era. It was the model’s hands—these misshapen blobs with stumpy, chipolata digits—or in some cases, a complete lack thereof—that suggested little promise in my artistic capabilities.

In a very harmless act that barely counts as teenage rebellion, I took Art anyway. Four years later, I could finally draw hands and left school with an A at A Level.

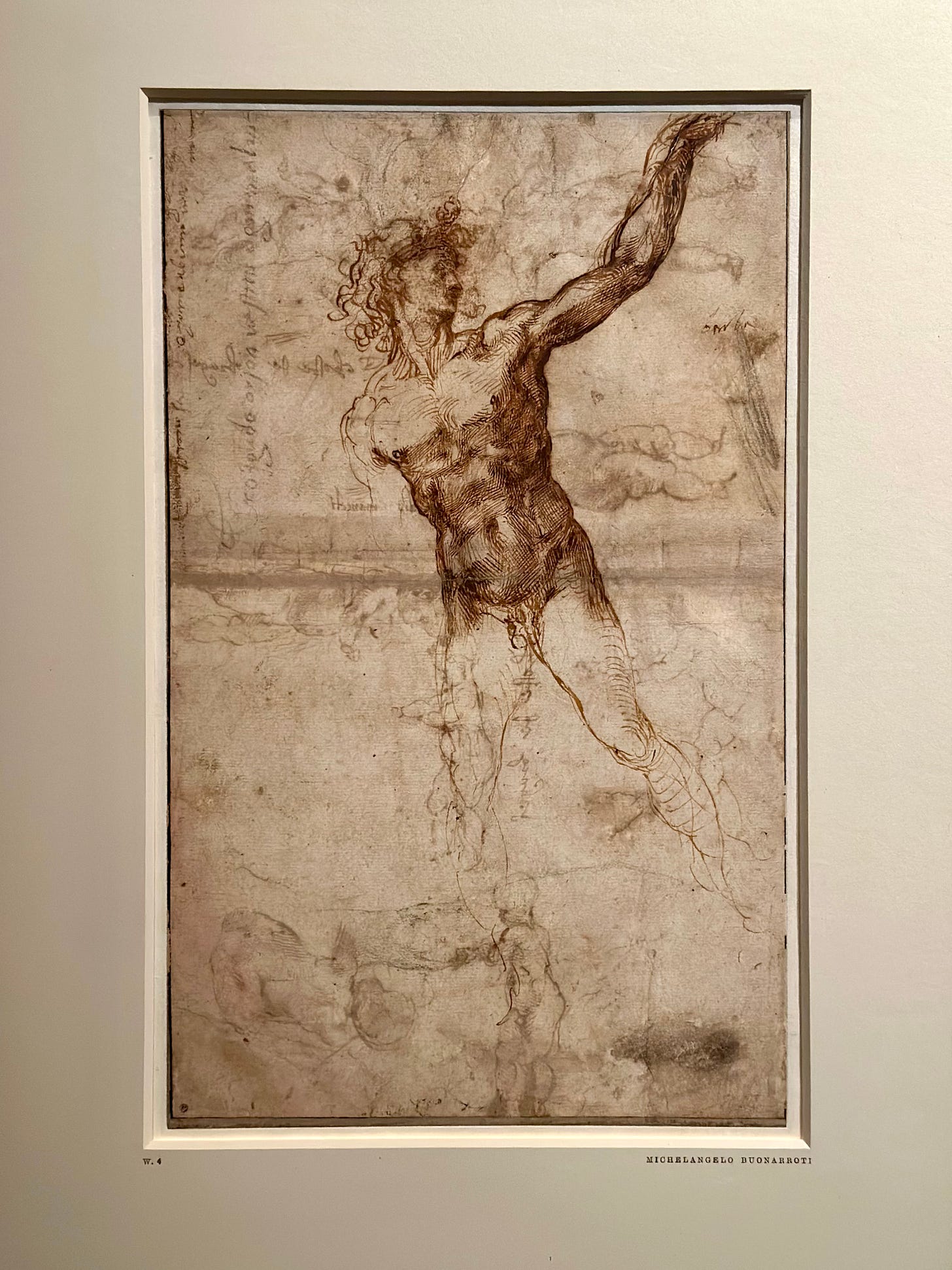

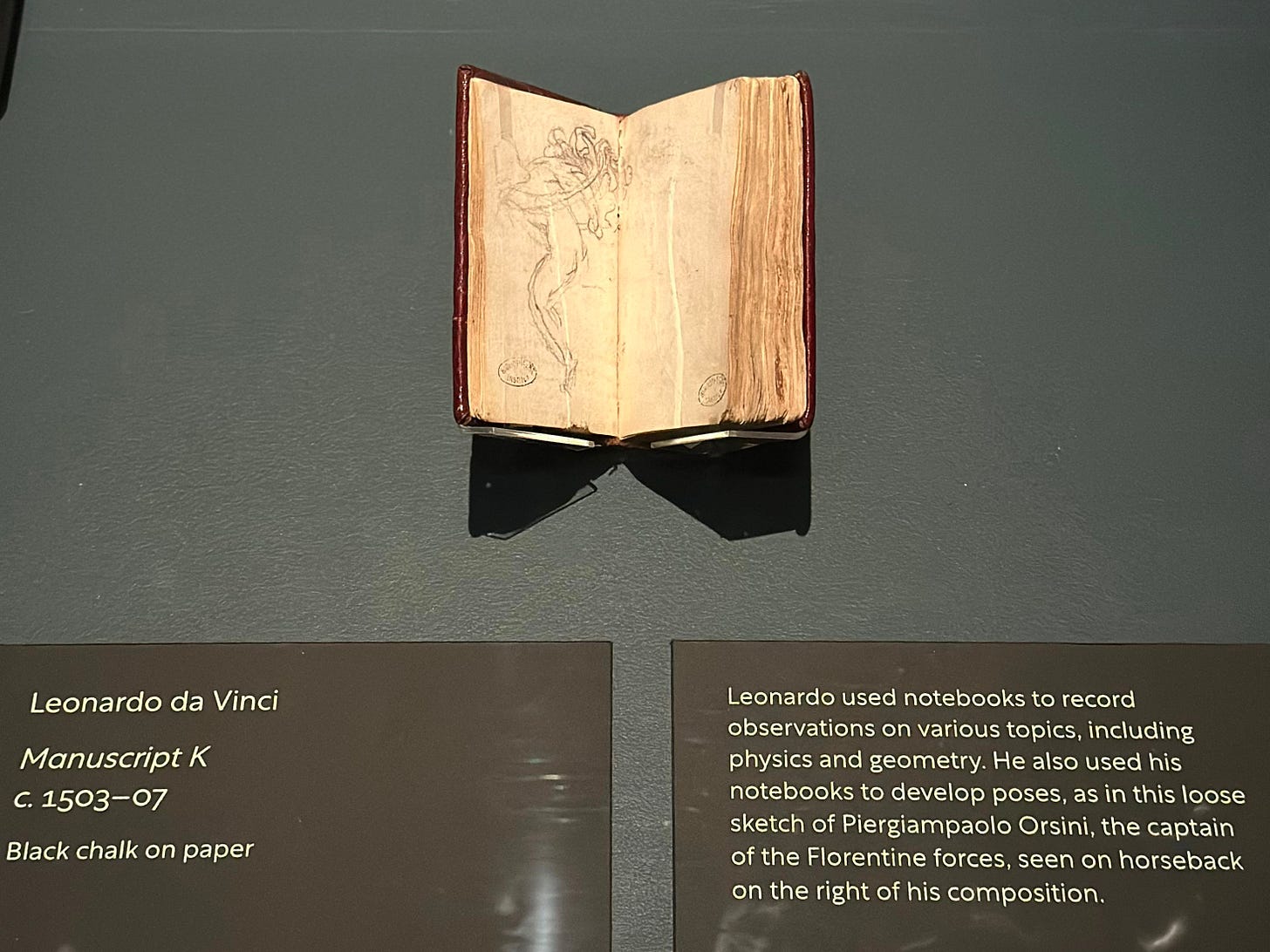

Fast forward to two weeks ago: I squeezed in a visit to Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael (Florence, c.1504) at the Royal Academy before it closed that weekend. It was a small exhibition, only three rooms, and what struck me immediately was that most of the featured works were preparatory sketches—or ‘studies’, as they are known—with not a sculpted David or Mona Lisa smile in sight.

I, for one, was pleasantly surprised by this. More than the polished, finished works we typically see in galleries, the loose, searching lines felt alive. It reminded me of the spiral-bound A3 portfolios I would fill for my Art projects at school. At the time it was rather onerous having to fill all of those pages, but thinking back, I have a delayed appreciation for how these works in progress would provide additional context to my finished exam artwork—evidence of curiosity, commitment, error, repetition, and, ideally, improvement.

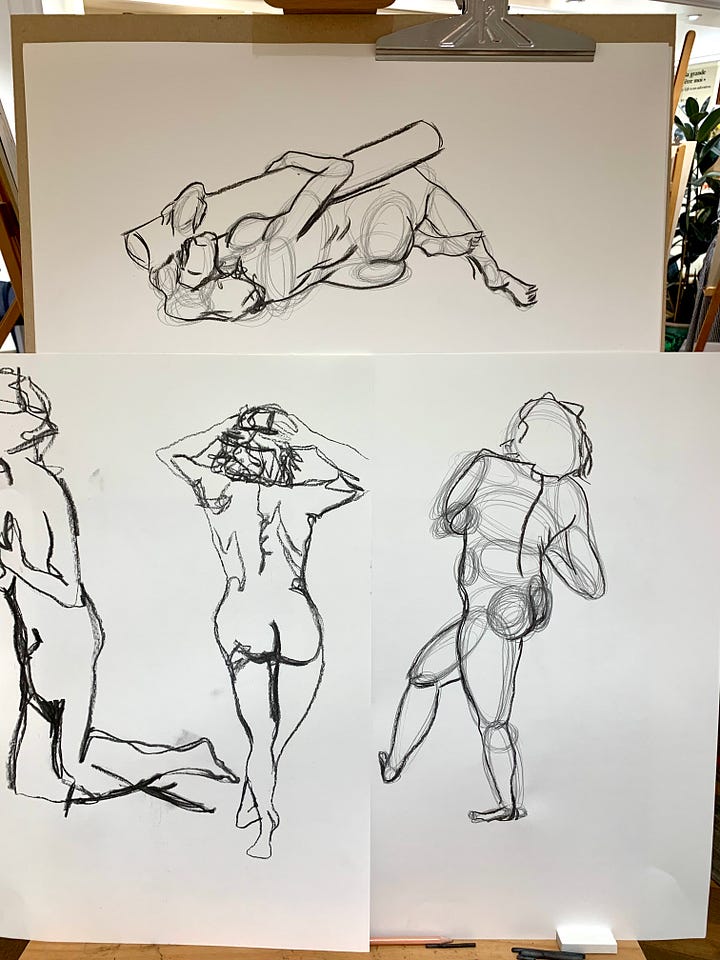

Seeing so many studies of these three Italian Renaissance titans was a reminder that true mastery comes with trial and error. Some were nothing more than repeated attempts at drawing the same arm, seeking the perfect pose and muscle flex—I could have stood and stared for hours.

Evidence of Michelangelo putting this effort in is rare, as the signage informed me that he ‘famously destroyed many of his drawings, presumably in an attempt to create the impression that his compositions were the product of artistic genius rather than meticulous preparation.’

This impulse to hide our process seems timeless—to conceal the evidence of trying, of learning.

Sketching became my medium of choice at school. I found my groove in monochrome lines and scribbled portraits, and discovered the satisfaction of drawing with pen and ink. It’s not a precise medium, often bleeding out or leaking on the page where it’s not meant to be. I even acquired my own set of Indian inks and pens with different-sized nibs. I had ideas, as a student with romantic notions of adulthood, of carrying them around with me when I travel. Alas, most of them never made it out of their Perspex box. Much like the drum kit I requested for my 16th birthday and had sold on by my 17th, my late teen attention span quickly moved on to the next thing.

But sketching has remained a recurring motif in my life. There’s been the odd holiday doodle when I did occasionally remember to bring a sketchbook with me; a day course on Portrait Drawing here or there; one or two Life Drawing classes to refresh those basic principles of capturing form in two dimensions. Not to mention my more recent penchant for fine-line tattoos, of which I have a growing collection on my right arm (also to my parents’ dismay).

Sketches aren’t meant to be flawless or remain within the lines. They’re alive in a way that paintings often aren’t. They preserve the kinetic energy of the human hand, arm, and body that attempts to transfer something seen or imagined into something static and still.

But where were we? Oh yeah, 1504. Young Raphael took a different approach from his predecessors when he arrived on the Florentine scene. He studied Michelangelo's work openly, using his observations, imitations, and in some cases, direct copies of another’s work to help him hone his craft. What's that theory—that if you do anything for 10,000 hours you'll become an expert in it? I wonder how many hours of work hung in those three chambers.

“Neither Leonardo nor Michelangelo’s mural was ever completed,” wrote one display. “All that survived are their preparatory drawings, many of which are assembled here.”

I fear that as adults, we tend to reveal things only when they are ‘completed’. Perhaps we feel that our time for learning has been and gone. Learning in public, at least. Even when the intention is to show a process—an Instagram account documenting a house renovation, or a YouTube channel tracking someone's fitness journey—there's an undercurrent that the finished form is where the value lies.

We discard the scraps of our hobbies, hide the receipts, wanting to be seen as having mastered something rather than in the process of mastering.

But if we’re hesitant to show our drafts and workings out, what happens when technology can summon ‘completed’ works instantly? How do we discern the human-made from the AI-generated? When one can conjure an entire essay in minutes, does it erase the value of trying altogether?

I use the word ‘conjure’ deliberately. Coincidentally (or perhaps not), I attended an event on Magic, Imagination and AI in the same week as my art field trip. The panellists discussed artificial intelligence through the lens of magic as otherness: it’s about seeking contact with something else. When interacting with AI, we’re not entirely sure whose intelligence it is, but it sure isn’t wholly ours.

That there are forces greater than humans at play is ingrained in our collective psyche, whether we buy into the literal existence of non-corporeal beings or treat them as figments of our imaginations. There’s something profoundly human in this desire to come into contact with something more than ourselves. Is AI not just the latest manifestation of this?

“Prompting is the ‘abracadabra’ of AI,” one person offered to the audience during the Q&A. In the 16th Century, Michelangelo destroyed his drawings to maintain an aura of genius. In the 21st, we can erase all traces of effort with a single click.

When we ask something of generative AI, it is like we’re casting a spell. Except, in doing so, we lose most of the magic.

Da Vinci and his contemporaries didn’t have AI image generators (even though their image is being used to market them), but their studies exude a kind of magic that is distinctively human—the compulsion to show up again and again, tweaking, reworking, improving, trying different angles, repeating until they’re ‘ready’ to commit it to canvas or stone.

There is magic, I feel, in these sketches being preserved for centuries. In enough people still caring in the digital age to curate and visit an exhibition of unfinished works from half a century ago. The evidence of human hands reaching toward mastery.

Reader, don’t mistake this for a rejection of generative AI tools—like many, I use them almost daily and am becoming increasingly dependent on them for certain tasks. But I’m realising, like any tool, it’s most powerful when combined with human taste and judgment. If we always defer to technology's quick solutions, we risk atrophying our own creative muscles.

I still want to see the crossed-out line and try to work out the word it’s masking. I still want to see ink bleeding onto the page. I want the footnotes and the side notes with interrupted thoughts that don’t quite fit; the blurry photos taken in a rushed moment of excitement that don’t make the grid. Give me the half-formed ideas that go nowhere—until they sit, ferment, and form something imperfect, something whole, its own work of art.

If we always wait until something is ‘completed,’ we never let others see the real magic of what we’re making.

I’ll make you a deal. Show me your studies, and I’ll show you mine.

other things I’m noodling on

This post was 70% ready when I published it

This essay does a great job of preserving the human touch in the AI debate

Currently reading before bed

Currently watching on Monday evenings

Wow loved this! So true that showing your workings / the messy process that took you to the end result is valuable but also often interesting to others

Loved this one!