I spent the past week in Cornwall with my mum and the dog. Holiday for her, workcation for me – though through efficient time management and claiming back some time owed in lieu, it ended up being lighter on the work, heavier on the -cation.

We stayed in a small village with “all the provisions”, which meant a post office and a pub by Cornish standards. Even the pub was only just reopening its doors after a year-long skirmish between old and new owners. So for the first half of the week, it was just a post office.

I spent much of the week in a state of boredom. Not bored – there’s a crucial difference, which my idleness gave me plenty of time to ponder.

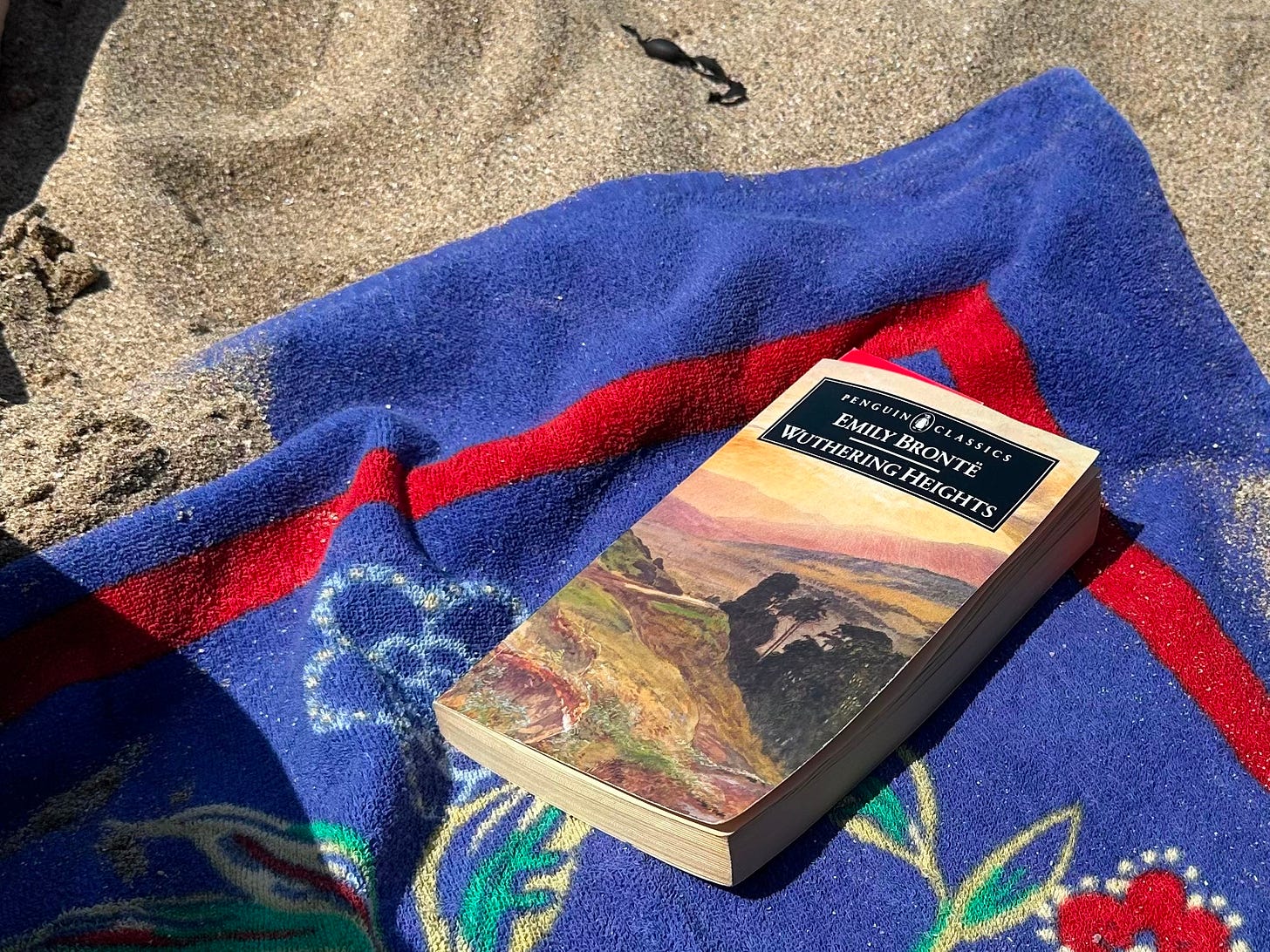

When we’re bored, we resign ourselves to the lack of stimulation and admit defeat. We start complaining like a petulant child. Woe is me, who has nothing to do! (Ok, maybe not those exact words – blame Emily Brontë.) But it is hard to say the words “I’m bored” out loud without it coming out like a whine. Go on, try it.

But being in boredom is quite different. It’s like the distinction between loneliness and solitude, which has been a subject of fascination for many writers (Gabriel García Márquez, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Stephen Batchelor come to mind). One happens to us, the other we choose. Loneliness arises from a lack of control, solitude is sought.

Similarly, when we’re in boredom, we’re still holding onto our agency. We’re on the cusp of ennui, but fighting the urge to blame our circumstances for it. We recognise that, as with most things, it’s only temporary, and there is a cure.

The antidote is curiosity. To start looking around for something, anything, to catch our attention.

We notice road signs with amusing names, like ‘Pityme’, debating whether that is pronounced phonetically (pity me) or in some whimsical west country way (pie-thyme). Passing the next junction, we wonder if the towns Chapel and Amble are as holy or leisurely as their names suggest.

We eavesdrop on our neighbours at the beach, shielded only by a windbreaker, as they navigate their picnic crisis: how does one eat coleslaw without the forks they forgot to pack?

We’re charmed by the signs of local businesses, warning patrons of the pasty-stealing seagulls, or using outright flattery to tempt us into checking out their accessories. We’re amused by the punny name of the local chippie, and doubley satisfied by the matching yellow car parked outside.

We’re stopped in our tracks when the setting sun casts our shadow over the overgrown grass, embedding us into the landscape.

Without the familiarities and distractions of home – be it housemates, housework, hobbies, admin, food shops, cooking, tv streaming – pulling at our attention, these small fascinations accumulate. We sink into what feels like a sacred boredom, an active listlessness, a willingness to be surprised by the mundane.

And somehow, despite doing very little, we leave feeling more fulfilled than if we’d packed a whole week of activity.